On a previously desolate part of the North Wessex Downs, Konrad Goess-Saurau has created a wildlife paradise

Konrad Goess-Saurau farms 2,000 acres of Wiltshire downland on the edge of Marlborough. Over 30 years he has transformed an intensive arable farm into an award-winning combination of profitable agricultural business and wildlife haven with 500 acres (about 25 per cent) devoted to conservation.

Since he bought Temple Farm estate in 1985, he has planted more than 23 miles of hedges and 1 million trees. To put this in perspective, at the 2015 General Election the government pledged to plant 11 million trees across the whole of the UK by 2020 and so far has managed 2.5 million.

Farm facts

- Location: Wiltshire

- Type of farming: Arable

- Acreage: 2,000

- Percentage in conservation: 25

- Funding grants: HLS, Forestry Commission, NIA, SWFBI, North Wessex Downs AONB

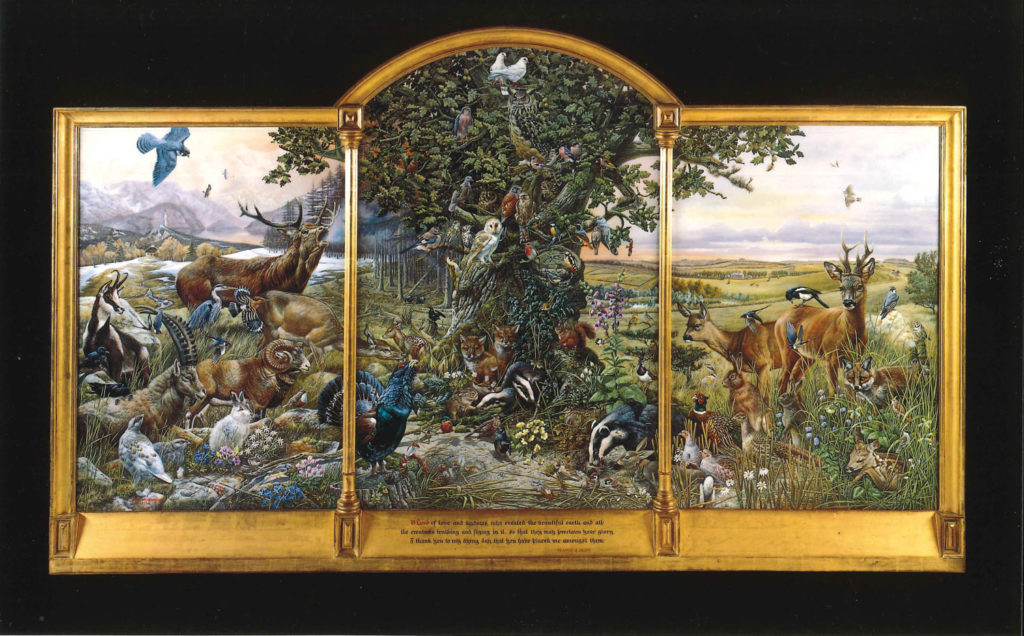

Growing up on an estate in Austria, the traditional hunting culture played a strong part in Konrad’s upbringing, instilling a love of wildlife and a conservation instinct. He has built a traditional Austrian-style chapel containing memorials to family members in a tranquil spot tucked into a slope on the farm. On the back wall is a beautiful painting depicting the animals of both the Austrian mountains and the Marlborough Downs.

The reintroduction of wildlife is in the family tradition. Konrad said: “In the 1950s, my grandfather reintroduced the Ibex to Austria after it had been wiped out through hunting. If you don’t re-create the habitat, you miss out on the delight of happening upon nature, unexpectedly coming upon a deer or a bird – these encounters are magical.”

Konrad started his transformation of the farm as soon as he arrived, but it was a gradual process: “When I first came it was desolate and so windy I didn’t get out of the car. There was nothing you’d expect from an English estate, not so much as a mouse.”

The land had been owned by English Farms, a business set up to maximise agricultural production after World War II by ploughing up the Wiltshire Downs. Prior to that, it had been largely grazed.

The first aim was to create a pheasant shoot with an emphasis on wildlife habitat. Konrad asked GWCT advisor Ian McCall, who had helped his brother in Austria, to work on the project alongside current chief executive Teresa Dent. He said: “The GWCT is very important. They are the first port of call on what to plant where, which cover crop mixes to use and how to manage gamebirds.”

Ian planned new covers and planting to wind-proof the few existing ones with shrubs round the edges. Hedges were put in consisting of two parallel rows of trees a couple of yards apart, creating a tunnel for the pheasants to move between drives. Other conservation measures on the estate include a mix of areas of long grass and grazing by rare breed White Park cattle. Some of the higher ground was sown with traditional grasses and left to revert to scrub, and the gorse and wildflowers have returned. Much of this is designated SSSI in part due to several prehistoric standing stones dating back to 5,000BC.

Konrad explained: “There was no grand plan and anyone embarking on a big project who says they got it right from the start is lying. What’s extraordinary is how little there was before and how much has returned.”

The creation of nine traditional, clay-lined dew ponds attracted wildfowl, and the area now boasts breeding populations of threatened birds including corn bunting, stone curlew, grey partridge and visiting short-eared owls, all of which had previously disappeared. Temple Farm’s headkeeper Phil Holborrow commented: “The RSPB were impressed when they counted 115 lapwings in addition to stone curlews, yellowhammers, turtle doves, tree sparrows and skylarks.”

Konrad is keen to prove that it’s possible make a profit in agriculture and still leave space for nature. The farm has abandoned conservation headlands, those areas in the field which are not sprayed, as they were struggling with the build up of weeds. Instead they decided to plant wild bird mixes where they had previously had headlands and keep them completely separate. Much of the 25 percent that’s not in production is on steep banks that would be very difficult to farm and taking the field margins out of production does not mean the farm is no longer profitable even if revenue is reduced.

Konrad explained: “If your intention is to spend the entire summer in St Tropez then you might need to farm right up to the field edge, but if you are happy to spend some of it in England, then why not create a long grass margin that is good for wildlife and nice to walk on?”

The farm is only viable if you include the agri-environment schemes, which help cover multiple costs including tree planting and maintenance, and drilling of annual cover crops. Konrad is keen that taxpayers should get value for money from environmental subsidies. Though he welcomes Michael Gove’s proposals to switch grants to environmental measures post-Brexit, he is concerned that the dual outcomes of high-quality food production and more wildlife must be achieved. “If you can no longer make a profit farming, there is a risk you will stop producing food and simply plant the whole farm with trees, then what has the nation achieved?”

At the same time, he would also like to see a more flexible approach from government agencies and one that rewards results. He explained: “On one occasion, I planted a 140-acre wood on a 3m-by-3m basis to ensure even growth. When we had finished, they wouldn’t give us the last 10 percent of the grant because it wasn’t planted 2m by 3m.”

There are plenty of footpaths through the estate from which walkers can enjoy the wildlife, but Konrad thinks it is important to have some parts of the farm where not even he or his keeper go. He said: “95 percent of people are happy with sticking to footpaths, and avoiding disturbance is key to conservation. We encourage visits from local schools and universities, but the right to roam anywhere would be damaging. Imagine people with dogs wandering everywhere during the songbird breeding season. I put this to the RSPB, which was pushing for greater access to private land at the time. I suggested we work together to create the Swindon bird-watching club. I offered to put up a hide on every pond on the farm and set up a website for bookings. We could then charge birdwatchers a subscription and split it between us. Sadly, the idea didn’t catch on.”

Temple shoot releases 6,000 pheasants and 6,000 partridges and shoots only cock birds in order to encourage the wild pheasant population. This method has clearly worked, with over 50 clutches counted last year. Predator control is a key element in Temple’s success story and and the work of head keeper Phil Holborrow keeping rats, foxes, rabbits, corvids, weasels, stoats and grey squirrels under control is essential to songbird survival.

Every year, five or six roebucks are culled to manage the population and Konrad’s cousins come over from Austria to help. He explained: “When

I was a child in Austria, we had many gamekeepers and their work revolved around maintaining a healthy deer population and conserving the surrounding nature. Since we were small boys we went deerstalking with our parents – my mother loved deer and all wildlife. These days some modern foresters see roe deer as a pest, but it is the most beautiful animal and if a few trees get nibbled that’s nature. A forest without deer is a dead forest.”

Recognition for Temple Farm’s remarkable transformation rightly came in 2010 when it was chosen to launch Natural England’s South West Farmland Bird Initiative (SWFBI), due to the abundance of key species on the estate. In 2012 along with 41 other farms on the Marlborough Downs, the estate was listed as one of only 12 Nature Improvement Areas (NIA) in the country, and in November 2013 it won gold in the Purdey Awards for Game and Conservation.

Konrad shows no sign of slowing down the tree planting and more holm oaks are planned for the slopes of the Temple Estate. He believes to achieve conservation success you have to have a passion for it. “It’s no good just doing it for the money. You have to see conservation as rewarding in its own right and genuinely want to see the wildlife return.”

This case study is taken from our e-book Working Conservationists, available to download here for just £1.99.